Historian pens her mother’s life in rural China

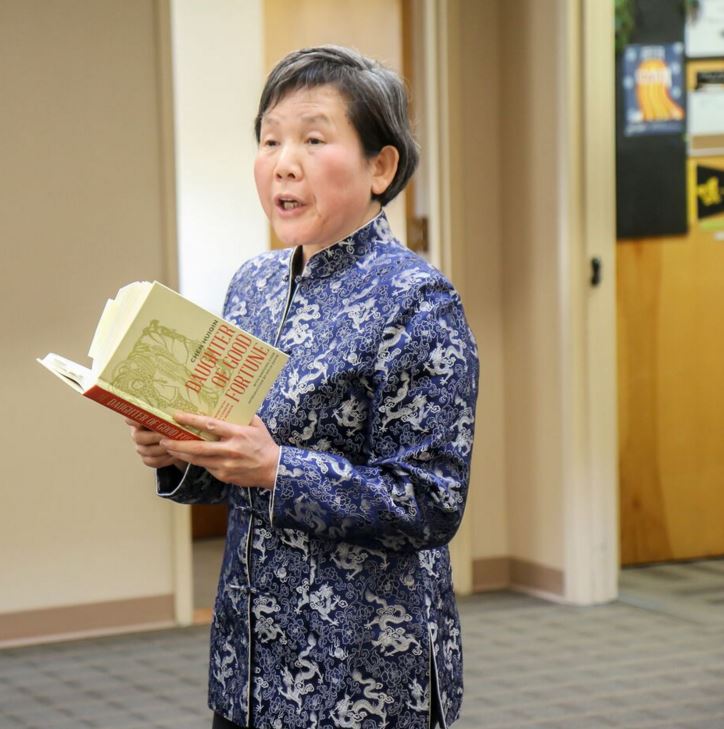

Shehong Chen discusses her book.

April 14, 2016

Shehong Chen didn’t set out to write a book about her mother.

But during her academic research on 20th-Century rural China, she stumbled into some first-account information about Chen Huiqin that was startling: Her mother’s life story coincided exactly with much of the work the historian was doing.

“Listening to my mother, I realized I actually had a story to write,” she said. “Her oral history matched perfectly with the research I was doing. I basically became the pen for my mother’s story.”

The result of her three years of interviewing her mother and documenting her words is Chen’s newest book, ‘Daughter of Good Fortune: A Twentieth Century Peasant Memoir,’ published last year by University of Washington Press. It has been praised as one of the best accounts of modern life in the Chinese countryside and how it has changed from the 1930s to the present. It is the only published peasant memoir in the country.

Chen is a native of Wangjialong, a suburb of Shanghai, and a professor of history at UMass-Lowell. She told the story of her book at a recent AIC event sponsored by the Honors Program.

To a packed audience in the West Wing last month, Chen said her mother was born in 1931 in the tiny village, where roads were dirt paths, electricity was non-existent, news came by word of mouth and water was exclusively drawn from wells. She was lucky enough to have a father who was a priest and was literate, and he taught her to read. With 500 written characters at her command, she was a rarity for the times.

When Japan invaded China in July 1937, she was just six years old. The takeover lasted eight years, and Chen Huiqin remembers as a young teen smearing her face with stove ash to avoid being taken and used by the soldiers as one of the ‘flower girls’.

She can vividly picture troops on horses marching through the village in 1945, at the start of the Communist takeover that banished the Japanese and resulted in societal changes such as land reform, where property was taken from those who had it and redistributed to those who didn’t. As the only child of a family considered well off, her life changed drastically.

She told Chen about her life through the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution that included a ‘Cleansing of the Class Ranks’ in 1968. Her father’s resistance resulted in him being jailed for nearly two years, a time that had a negative ripple effect on the family and the community. Her grandfather, in particular, was singled out by the government and was forced to inhale dangerous factory chemicals that the family believes resulted in his death by stomach cancer after just one year.

The 1984 Economic Reforms brought yet more cultural changes, and the family, like many others, moved from the rural area into Shanghai, where Chen’s mother lives in comfort in a modern townhouse. The village was torn down for economic expansion.

Chen said that despite all of the changes, her family and others still live by Chinese traditions, honoring their ancestors with gifts, including miniature elaborate paper houses.

Writing her mother’s story not only filled in many details of her research about cultural and political changes in China, it also proved to be an eye-opener about her own life.

“This work has had a tremendous impact on me personally,” she said. “I learned so much about my mother, about her endurance and her strength. I see that compared to how my mother lived her life, nothing is too difficult.

“Writing this book made me realize who I am and what my concept of the Chinese culture is.”

Born in 1954, Chen came to the United States in 1984 for college, earning a master’s degree in international politics at the University of Utah. She returned to China and taught political science for five years, coming back in 1992 and earning a doctorate in history in 1997. Leon Nguyen

Leon Nguyen